A potted history of Málaga

Empires, revolutions and riots. Wines, oil and anchovies...

Málaga is one of Europe's most ancient cities having been occupied and active commercially for almost 3000 years. It has undergone successive waves of colonisation in that time and was under the dominion of the Phoenicians and Greeks, and later the Carthaginians. Even before the Roman conquest, Málaga, or Malaka as it was known in the ancient world, was famed for its fish salting, its figs and its wines. It was (and still is) the most significant western trading port on the Mediterranean.

The Romans colonised the area in 218BC, but allowed Málaga to become a city intergrated into the republic, with its own statutes. While it became Romanized the freeborn Malagueños had automatic right of Roman citizenship and the town flourished commercially and culturally. Nowhere is this more evident than in Málaga's centre where the huge theatre below the walls of the Moorish castle give testament to the importance and size of its wealth to be able to support such cultural institutions. The theatre was operative for nearly 400 years and then lost to history until 1951, incredibly. Many of the remaining stones disappeared into the construction of the Moorish Alcazaba above it, leaving little visible trace for 1700 years.

Its wealth was based on agriculture in the rich Guadalhorce valley, its abundant fisheries and the wines and oils from the nearby mountains. Málaga has been synonomous with the anchovy for nearly its entire existence. In Roman times the fermented fish paste known as Garum was a delicacy renowned all over the ancient world. There is evidence of its manufacture all along the Spanish coast to this day, and the town had strategic importance in victualling the galleons on their way to the northern reaches of the Empire. Málaga was a cosmopolitan town, and under the Roman rule, other pagan tribes and cultures co-existed, and early Christianity laid down strong foundations here during the Roman period. The Spanish language, its legal principles and its main religion date from this era, despite the extraordinary interegnum of eight centuries of Islamic Moorish rule.

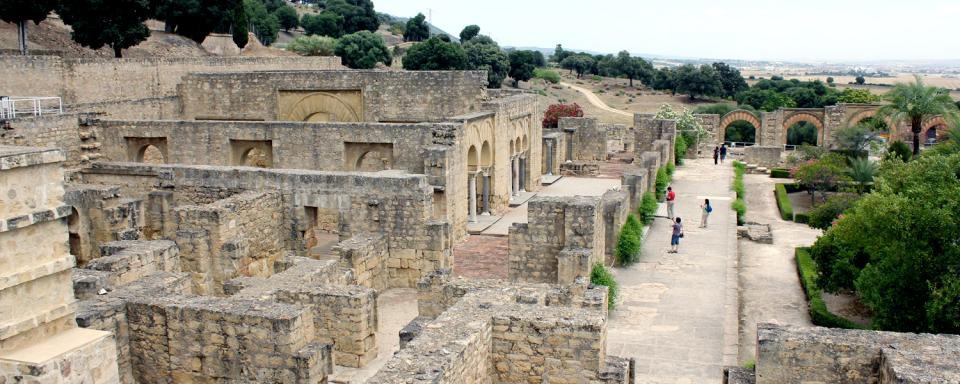

As the Roman empire dissolved, various tribes from the north crossed the Pyrenees to fill the power vacuum and it was eventually the Visigoths who gained the upper hand. In adopting Málaga they actually maintained much of the Roman institutions and laws during the 500's until the Byzantine empire conquered the region and re-established an empire, Christian in basis with Roman legal codes. This stable and successful world survived until 615 when the Visigoths returned with a vengeance and the city was sacked and destroyed. The province was left in a parlous state, its agriculture and trade decimated. A century later, Islamic adventurers from Persia, leading armies largely drawn from Berber tribes in North Africa started to raid the region from over the water. The Visigoth King Roderic, weakened by internal feuds, was unable to resist them and the Moors were able to gain rapid ground and conquer the whole of the peninsula by 718, getting as far as Tours in France by 732, where they were turned back by Charlemagne. The kingdom of Al Andaluz that they founded lasted until 1492, and endured much upheaval, civil war, tribal strife, and religious conflict. Under the Caliphate of Cordoba it was a united kingdom for barely more than a 100 years before religious civil war tore the Caliphate apart and saw the destruction of Madinat Alzahra, the Caliph's capital, in 1009 by an extremist Berber minority, possibly the earliest case of what some commentators like to call 'Islamic fundamentalism'! What had become the most populous and advanced city on earth, with irrigated agriculture, maths, science, astronomy, literature and gastronomy flourishing like never before, soon fell into a diverse realm of squabbling tribal and noble fiefdoms.

Málaga was an independent statelet or Taifa for 200 years, before being taken in 1239 under the dominion of the Nasrid dynasty based in Granada which was by now the foremost city of Al Andalus, and became the longest lasting Moorish Kingdom until vanquished by the Catholic Kings, Ferdinand and Isabella in 1492. It gave the Kingdom a major seaport and Málaga flourished again on international trade. It became a centre of shipbuilding and ceramic manufacture. Its shipyard was world-renowned, with its huge horse shoe arched portals allowing ships to sail into a covered dock. Today the site is actually the Mercado de Atarazanas, one of the cities iconic attractions and the main food market. The spectacular arch in the market's main facade is a reconstruction of the principal entrance of the old shipyard which was demolished, after over 600 years of use, and rebuilt in 1879. It is nonetheless a spectacular and cherished feature of the city.

In 1487 the city capitulated to the Castillian crown after a siege of several months. A handful of principal families were allowed to remain but by and large the provinces' lands were divided up among Christian warriors' families. Under the treaties signed on the final conquest of 1492, Málaga's remaining Muslim population accepted subjugation and in return for paying taxes, releasing Christian captives, and later on abandoning their religious faith, they were allowed to keep their property and businesses. Eventually after tensions and various phases of religious suppression, the 'Moriscos' were obliged to fully convert or be expelled. Málaga still flourished through its continued connections with Genoese merchants and North Africa, and its prized exports of raisins and wines.

The 1600's saw the city struggle as Spain militarily suffered setbacks in Gibraltar in 1704, and the expulsion of the Moors had weakened the city's commercial fabric. There were ecological disasters, earthquakes and economic issues that all strained the city. Málaga's port became more important as a military base. The port remained the economic lynchpin and its expansion and size laid the basis for a 19th century boom in the city. Not before the convulsions of the Spanish state had left their mark. Málaga was left battered and ravaged by Napoleonic forces. There then followed two revolutions against the absolutism of the Spanish Monarchy where the independent outward-looking spirit of the port city put it very much in opposition to the crown. This was characterised by General José Maria Torrijos who fought the repressive Ferdinand VII, but was betrayed and executed on the beach 1831. His remains are buried beneath the main square of Plaza de la Merced and he is still celebrated as a Málaga hero.

A further revolt happened in 1835, and in 1836 the city seized ecclesiastical properties which accounted for an entire quarter of the old city. Many were demolished and the city was modernized, with new squares and avenues. It is at this moment that Málaga becomes the leader in Spain's industrial revolution. Commerce and manufacturing increased and the city modernised transport links and infrastructure and further expanded the port to its current dimensions, building a whole new commercial quarter on landfill, leaving the Cathedral that once dominated the seafront significantly inland. This now forms the Soho barrio of the city. Málaga rode out two more serious rebellions and constitutional upheavals, with the politics of the city being on the progressive side, with its large urban proletariat and peasant class. But time was catching up, and by the late 19th century commodity prices forced the collapse of the iron works, competition from cities in the north drove it down, and the dreaded phylloxera fungal blight all but wiped out its enormous wine industry. The impact on the ecology of the region and the rural population and associated city industries was profound. Erosion, deforestation and flooding increased dramatically. The lower classes suffered terribly and left in droves for elsewhere in Europe or the Americas. Ironically Spain's economy received a huge boost from the 1914-18 war as it supplied all sides in the war with materials. But the affluence was largely reserved for the ruling oligarchies and merchant classes. The progressive forces of the mid 19th century had lost their force in Málaga, and the region was dominated by elitism, political cronyism and corruption. (One might argue not too much has changed!) The lower classes were largely illiterate, and as the economy contracted and industry fell away, the rest of the world started to leave it behind. The great flu pandemic of 1918 also further debilitated the country, one that hadn't even suffered in the war like others.

During the 20's the city recovered somewhat as the dictatorship of Primero Rivera revitalised sectors of the economy, but then once again cyclical crises of the economy, agriculture and the Wall Street crash had an impact. This was the time of great social change in Spain, with anti-monarchist and republican sentiment building in the lower classes. Socialist, communist, and anarchist groups became more vociferous and influential and elected the Republican party to power in 1931, provoking the King to flee. One thing that characterized the Republican forces was anti-clericism, and the election victory provoked riots against church property nation-wide. None more so than in Málaga where priceless heritage, churches, convents, libraries, sculpture and painting were all torched by the angry mobs. Málaga elected the first communist member of the parliament in 1933, and by now had earned the nickname 'Red Málaga'. Successive changes of government between right and left made for a highly polarised society rife with political conflict and intrigue. The second republican government struggled to keep a lid on the country and its own anarchist allies who destabilised things further. As the country slid into Civil War, Málaga was firmly on the Republican side. In February 1937 the Francist forces laid siege to Málaga, with the help of Italian fascist troops and Moroccan conscripts and the city capitulated in eight days, forcing thousands of refugees out into the country. Many made for Almería along the coast road where they were strafed and massacred by the Francist gunboats and artillery. Hundreds of Malagueños died. The Spanish Civil War was bitter and brutal. Atrocities against civilians, clergy and POW's were rampant on all sides. The divisions sown were bitter and deep. Franco's victory allowed him to cement an alliance of the right-wing parties and create a one-party state run by the new Falange. Left-wing parties and trade unions were banned. 151,000 Republican political prisoners were executed between 1939 and 1943 alone. To this day there are mass graves on the edges of Málaga containing undocumented citizens summarily executed or disappeared, a practice that continued into the 1950's. Málaga's and Spain's scars are actually just beneath the surface.

Spain became an isolated, backward and insular dictatorship, rampant with poverty and repression. When you see the vibrant, relaxed, welcoming and stylish city that is Málaga today, it is hard to imagine the extraordinary waves of conflict and repression, tragedy and crisis, regeneration and recovery that have rolled across the city for centuries.

The release from the seemingly fatal slide into desperate poverty and abandonment that Andalucia suffered after the civil war came from tourism. Franco saw it as a controllable way of bringing back some kind of development and prosperity, as there was little industry left, agriculture was degraded and backward. Tourism put Málaga and its coast firmly back on the map in the 20th century. It was chaotic, sometimes damaging and short-sighted development but it did work. Franco died in 1975 and once the new King Juan Carlos had guided Spain to democracy and the European Union, Spain finally joined the club of nations as an equal.

Málaga today is markedly different from even a few years ago. EU funds have provided outstanding infrastructure connections of motorway and high-speed trains. Málaga airport is one of the world's busiest. A technology park is steadily creating a European silicon valley. The old interior has seen its villages empty out, and instead of emigrating to the Americas, young Spaniards head to the Costas for employment and a vibrant life. Despite the battering of the economic recession of the noughties, Málaga stands unbent, defiant and optimistic. Its town and province bubble with colour, enthusiasm, culture and leisure. A gastronomic revival has given the province no fewer than 8 Michelin stars, 8 more than the City of Manchester! Its football team threatened to be good for a moment, until Manchester City lured their manager away. Must have been revenge.

Málaga today is a European destination par excellence. Yet you don't have to look far to see the echoes of time gone by, the secrets of the past are thinly veiled. With all its history pulled around it like a great shawl, Málaga blinks, smiling into the beautiful sunlight, looking forward to a brighter, and definitely more fun future.

Come and visit.